Introduction

Aneurin Bevan, the health minister in Clement Attlee’s Labour Government, introduced the NHS in 1948 after some years of debate. It was the world’s first universal healthcare system and had a budget of £437 million (equivalent to £20 billion now). In fact it is now £192 billion. The basic premise was if disease were eradicated, the nation’s prosperity would thrive. That will be 80 years ago in 3 years. So the majority of people alive have only known this service for delivering their healthcare. Within 3 years it was considered unaffordable, and was never copied internationally. But it is still free at the point of delivery, cradle to grave. And medicine has never been as creative, with this being the most amazing era in which to learn medicine. The NHS in which we practice our medicine does face issues and challenges however. The issues I perceive as important are listed in my order of priority.

1 Outcomes

From a medical point of view there is no doubt that we have poorer outcomes than many developed nations. This is almost certainly linked to access, ie it takes longer to get a diagnosis when it is harder to get to see (eg) an expert and/or get a scan, or an angiogram or endoscopy. More of this in issue no 2.

On cardiovascular deaths, in 2019 the UK recorded 132.3 per 100,000 population compared to 91.4 in France and 77.03 in Japan. In 2022, 5 year survival rates for lung cancer were 9.6% in the UK (internationally bottom) compared with 37.2% in Mauritius.

For gastric cancer it was 18.5% in the UK, and 57.9% in South Korea. For prostate cancer it was 83.2% in the UK, and 100% in Tunisia. These are condemning data and statistics we really cannot ignore.

| Medical issue | Year | UK | Other |

| Cardio-vascular | 2019 | 132 deaths per 100,000 | 77 deaths per 100,000 Japan |

| Lung cancer | 2022 | 9.6% 5 year survival | 37.2% Mauritius |

| Gastric cancer | 2022 | 18.5% 5 year survival | 57.9% S Korea |

| Prostate cancer | 2022 | 83.2% 5 year survival | 100% Tunisia |

2 Access

One of the big issues for the NHS is that there are very limited points of entry, ie 999, Emergency Departments (ED), GP and private healthcare. In more recent times we have seen walk-in-centres develop, but typically they do not provide treatment beyond primary care, or onward referral.

Our GPs are the traditional gate-keepers, and this is how they were perceived in public health. But their work today is very extensive and under-resourced. People in 2025 have been trained to want ‘click and get’ by eBay, Amazon and digital TV. The NHS is massively behind the curve, maybe by over 20 years.

This limited access compares unfavourably with other national systems where there are easier entry points to specialist services. In France, for example, one can simply telephone a specialist and fix an appointment, often within a few days. In fact there is an app (Doctolib) that will locate suitable consultant appointments in your locality. It sources video or in-person consultations which can then be booked. This is possible because the system is devolved rather than centralised. Their Carte Vitale is the national card that allows direct settlement of bills and so this is presented at the point of consultation and the bill is paid.’

The UK access ‘vacuum’ is driving private healthcare uptake, in family medicine, surgical, dental, and pharmaceutical care, both here and abroad. Those who cannot afford private healthcare either wait, or choose to visit the only other choice, their local EDs, resulting in increased congestion and many inappropriate attendances. And, of course, waiting allows diseases to progress. The introduction of John Major’s ‘Patient’s Charter’ over 30 years ago, then the subsequent pursuit of targets has understandably developed people’s sense of entitlement and expectation. But this often cannot be matched by the capacity to deliver care. The mantra ‘free at the point of delivery’ is an often heard political statement, but is actually less meaningful when delivery is just not there.

One reason we struggle to deliver is that between 1987/8 and 2016/17 the total number of NHS acute hospital beds fell by an eye-watering 52%, from 299,364 to 142,568. This has created a bottle-neck from GP to ambulance then to ED to acute beds. More later.

3 Cost and productivity

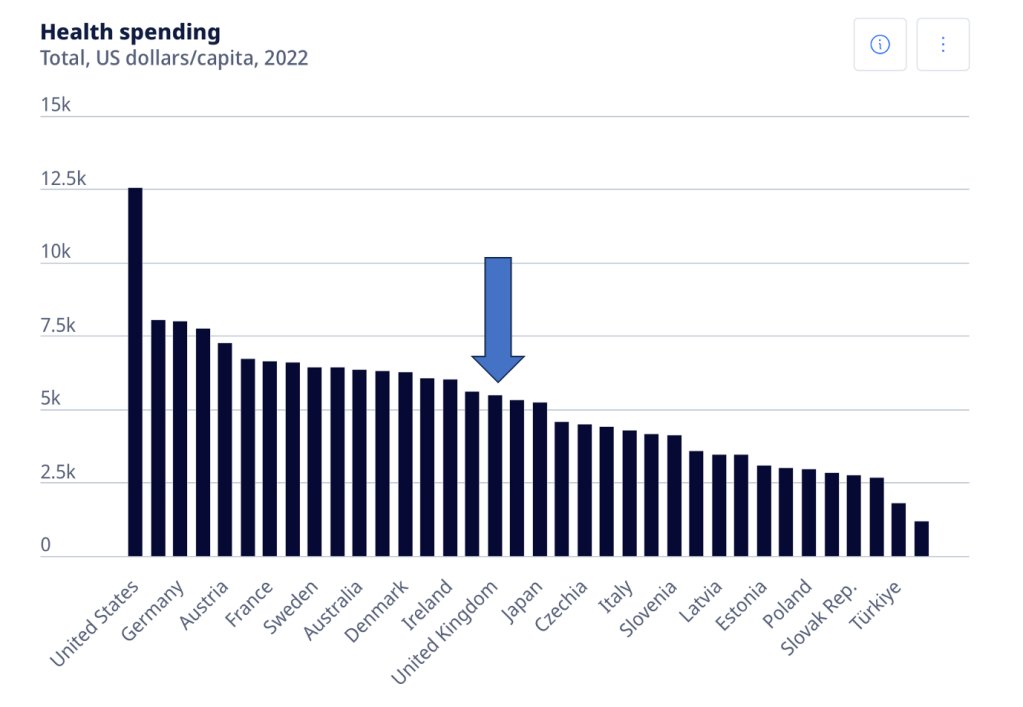

International comparison regarding funding shows the NHS funding is not as bad as often stated, £192billion is massive. Looking at comparison with an OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) recent analysis we sit on the median for both spending per capita and % of GDP spent on health, against a group of other developed nations.

Given this level of spending, why are we a long way behind our neighbours in outcomes? The answer may lie in productivity and investment. For example, we invest far less in vital equipment such as MRI scanners than most other nations. On CT and MRI scanners we were OECD bottom in 2016. And these are vital to access early diagnosis and subsequent outcomes as we have seen.

So if we are median funded, where does the money go? One clue is that our NHS spends around 65 per cent of its budget on staff, maybe more than we need. But a more sobering consideration is that the number of backroom staff in the health service has been creeping up, and is now almost 50% per cent meaning that only 50% are clinically trained staff who actually deliver direct care. The need for staff to monitor targets, waiting lists and performance is a possible cause for this. But see section 7.

4 Increasing elderly population

Life expectancy is changing rapidly. In 1900, the average life expectancy of a newborn was 32 years. It is now 76 for a man and 80 for a woman, with significant rises predicted to one in 5 reaching 100 very soon. Social beds are desperately needed to off-load acute beds. Again, this has it’s effect on ED.

Social bed funding is a can which has been kicked down the road for a long time. It is expensive, with funding models contested. And we would struggle to train and deploy suitable staff in sufficient numbers.

We desperately need legal migrant workers to work in this sector, but this is never discussed, possibly due to the political sensitivity of discussing anything to do with migration.

This issue is inevitably going to increase, regardless of how we might ignore it. Assisted dying is seen by some as a solution, and this is weakening the resolve of some MPs to support a well-meaning bill.

5 Obesity

Obesity greatly increases the risks of type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, all forms of cancer, osteoarthritis, the need for joint replacement, hypertension, renal disease, vascular disease and stroke.

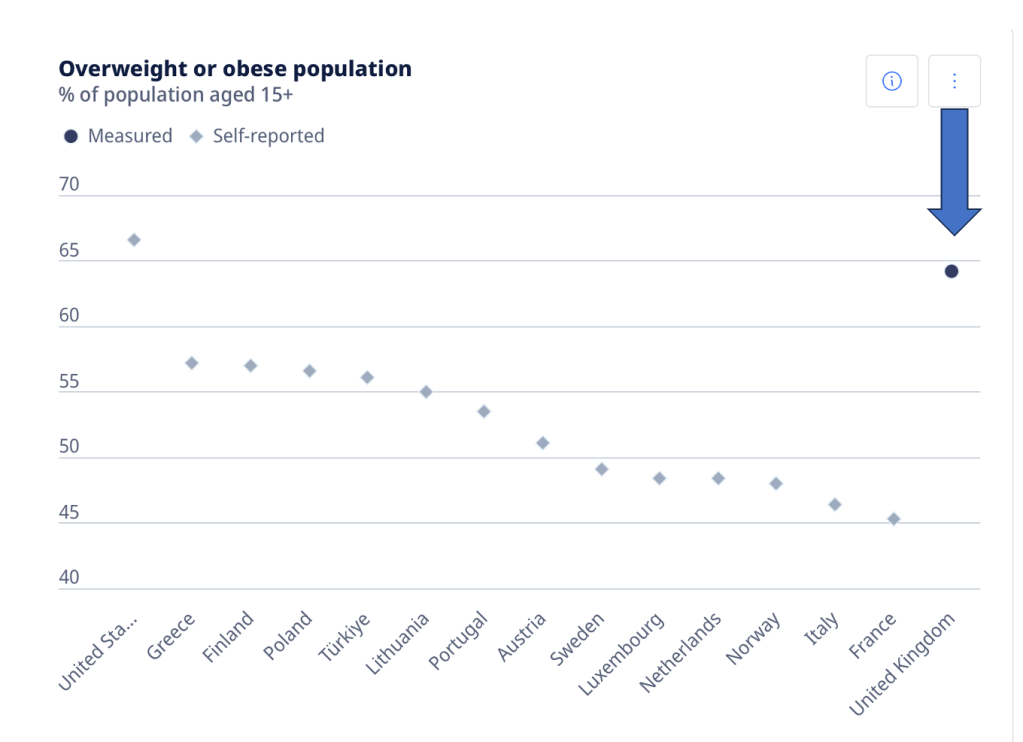

Right now 10% of NHS drug spending is devoted to treating type 2 diabetes, and the overall bill for all types of medication and devices to treat diabetes has reached more than £1 billion, representing a 68% increase in 10 years. In obesity we are second only to the USA. However, globally, many nations being affected by increasing obesity are developing nations. Perhaps due to poor diet, fizzy drinks and inadequate health education.

6 Capacity

On various metrics we have poor capacity. Britain has 2.8 doctors per 1,000 people, compared with an OECD average of 3.5 doctors. And we are not training the numbers needed for the coming years.

Bed numbers are also among the lowest, with 2.5 per 100,000 people, compared with an OECD average of 4.7. The low numbers of acute beds was driven in the 80’s and 90’s by the belief that laparoscopic surgery would mean lengths of stay would plummet. Whilst this is true – cholecystectomy meant at least a 7 day stay in hospital in 1980, now it is often done as a day case – this efficiency has been more than wiped out by our burgeoning aging population. There was a simple failure to see the demographic elderly onslaught.

OECD report that the UK has the second lowest number of beds and doctors in Europe compared with its population.

As noted above our numbers of CT and MRI scanners left us OECD bottom in 2016. On residential care beds we are 6th from bottom. This all means that the acute sector is under constant pressure, our EDs are congested as (a) too many people attend unnecessarily and (b) patients can’t be moved into beds as they are blocked by elderly patients waiting for residential care beds.

Add to this the permanent loss of cottage hospitals, mostly based on the combination of cost savings, short term gain from 4sale of the land and concerns over risk management.

7 Megalithic

With 1.4 million staff, the NHS is the biggest employer in Europe. This creates a wage bill that is greater than any other health system in Europe. It is very different from the devolved French system where consultants are free to run their own businesses, providing their own administrative support, and taking their own business risks. A megalithic system is hard to manage, even more so when it has complex goals. Amazon, as a comparison, is bigger but has a very limited business model. The NHS’s budget of £192 billion ($243 billion) puts it on a comparative footing with moderate sized nations such as Greece ($242 billion GDP) and more than Qatar ($213 billion GDP).

The question is whether such a massive structure with very complex goals can be run effectively and efficiently. AI may give us a way forward, particularly for monitoring targets and performance which really do not need staff to calculate. But right now the jury is out.

8 Litigation costs

The litigation budget assigned for 2025 is £2.8 billion, almost 1.5% of the entire NHS budget, and larger than Burger King (revenue £1billion), Tarmac (£2billion) and Lamborghini (£2billion). This is an eye-watering haemorrhage from NHS coffers.

Are there any solutions?

It is good to identify the problems but if I think I am a health guru, are there any good messages? I think so. But some courage will be needed!

Let’s look at the advantages our system gives us …

1 Data

The megalithic system is unique internationally and enables us to sell mass anonymous national data, outcomes and treatments. We are the only nation on earth that can do this. And the data is worth many millions.

2 Artificial Intelligence

We are world leaders in AI. The EU has just shot itself in the foot by their over-cautious regulation. AI could readily fix our big problem of poor access, hence outcomes. For example, a 40 a day smoker with a persistent cough could automatically be directed to have a chest x-ray (interpreted by AI), then a respiratory consultation, bypassing a GP referral. Ditto many conditions such as breast lump, blood in the urine etc. And we can also earn internationally from our expertise.

3 Private investment

We have to get over our distaste of private investment and realise that without it, social care beds will never materialise. In every other area of life we acknowledge how vital the market economy and private investment is. Why have we become so left-wing as to deny this way forward? The eye watering costs, ramping up with every year of elderly people mean that state funded social care beds will never materialise. And if that is true our hospitals will be log-jammed. For ever.

So, courageous action is required please politicians. Look out for the wise ones!

Leave a comment